- Home

- M. Anjelais

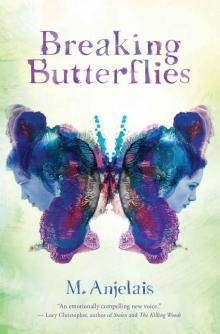

Breaking Butterflies Page 9

Breaking Butterflies Read online

Page 9

“It’s all right,” Leigh said, and she went on stroking his hair, smoothing down those blond waves that were so like her own.

“I’m dying,” Cadence whimpered into her shoulder. “I’m going to die.”

“I know, Cay. I’m so sorry,” she said, kissing the top of his head. He sniffled and turned in her arms to look at me. His face was streaked with tears, his hair sticking to the damp skin of his hollow cheeks.

“Sphinxie,” he said, holding out his hand to me. “Please forgive me.”

Only a moment ago he had been tall and frightening, furious and delighted all at once. He had shoved me, and I had sat on the floor of the attic with his artwork all around me, remembering the feeling of the cold blade slicing into my cheek. He had looked eager and hungry, and I had thought he was going to hurt me again. But now he was the one on the floor, quivering and pitiful. He had shrunk himself, becoming suddenly fragile, a rabid dog that had lain down suddenly, tail tucked between its legs. I took a deep breath and knelt next to him and Leigh on the floor.

I let him wrap his arms around me, let him beg me to forgive him, let him attempt to be remorseful. I was years older than him inside my head, whole and complete, and he was so young and terrible and raw. His hair was brushing against my face, tickling my skin. That made it worse somehow; he had gotten up that morning and showered and dressed, and walked downstairs and eaten breakfast, done everything perfectly, but then he had fallen apart. He was talented and bright and shining, but he had failed before he had even started.

“Don’t be mad at me, Sphinxie,” he said into my ear, his voice still trembling, his arms holding me tightly. “Please. I need you here.”

“It’s okay,” I heard myself telling him, my heartbeat pounding in my ears. “I’m not mad.”

I really decided it then, on the floor of the attic, when I told him that I wasn’t angry. But it was later that day, when we were all in the living room downstairs, that I realized it. My mother and Leigh were watching a sitcom on television, filling up their eyes with the antics of people who didn’t exist, and Cadence and I were reading: I had a novel with a picture of pink high heels on the front, while Cadence was flipping through The Picture of Dorian Gray. I had my iPod out, the earbuds stuck firmly in my ears, shuffling slowly through my songs.

And then the nurse comes round, and everyone lifts their heads, sang a soft male voice, mingling with piano that sounded like water overflowing past the edge of a sink. “What Sarah Said,” by Death Cab for Cutie. They weren’t my favorite band, but they were soft and good to listen to while reading. But I’m thinking of what Sarah said … that love is watching someone die. I looked up. Cadence turned a page in his book. Outside the wide living-room window, a flock of little birds descended on Leigh’s lawn and pecked the ground.

So who’s gonna watch you die? asked the singer’s voice, and I lowered my book. The digital camera was sitting on the coffee table. I picked it up, slowly slid it out of its case. Cadence’s eyes moved back and forth, following the words on the page, and I turned on the camera.

So who’s gonna watch you die? I focused the camera on the cover of his book, then moved up to his face, filming those striking eyes as they went back and forth, back and forth. He looked intent, firmly interested in the words on the pages before him, his lips parted slightly, peaceful — or as close to peaceful as he could come.

So who’s gonna watch you die? I kept the camera on him for a moment longer, then stopped before he could look up and notice me. He turned another page. And I thought of the way he had broken down in the attic, the torrent of emotion that he had released. And there was less than a year left, and even now the hands of the clock on the kitchen wall were moving, and the stove clock was changing, new numbers popping up. Time was flowing, rapidly, like the running notes of the piano … flowing, flowing, overflowing. The huge canvas in the attic filling up every day with more blue. Cadence, thinner, paler, losing his grip further every second. He had less than a year, and that meant I had less than a year to understand him, to know him, to do whatever I could for him. And love, the song had said, was watching someone die.

So who’s gonna watch you die? There — that was when I knew. I was not going to leave at the end of the week. My mother would have to get on the plane and go back home without me, because I was staying. I was not going to leave until Cadence was gone.

But why? My mind was swirling even as I felt invisible threads tie me down to Leigh’s house, securing my position. I was perfectly capable of leaving at the end of the week, of getting on that plane and leaving Cadence behind forever. I would never see him again, never need to fear him again, never need to let myself think about what could have been. I could do what everyone would say I should do: Move on. I had school. I had friends. I was normal, wasn’t I? And I had done my part, I had done my good deed and visited him at his request. It was as simple as that.

And yet I was beginning to realize that I was not as simple a person as I’d always believed I was. My entire life I had been clinging to my belief in my ordinary existence, covering up fears and past memories and emotions as I smeared concealer over my scar morning after morning. I was my mother’s good girl, my school’s nobody, another pair of feet on the soccer team. And I’d been born right and raised right and I shared my toys and I didn’t sneak out at night and my eyes weren’t full of ice. Ordinary. And yet there was nothing ordinary about my mother’s plan, nothing ordinary about the situation it had put me in, nothing ordinary about Cadence and me.

I was older now. I was sixteen. Sixteen. I knew things. My feelings were changing, dotted with question marks. I could form my own opinions. I wanted to make my own way, my own ending. There was this thing called love that I was beginning to understand was more complicated than a boy and girl making out after school, than a mother kissing her daughter on the forehead at bedtime. Love could be painful, frightening.

I could go home. I could keep on covering my scar. I could listen to my mother forever. It was an option … a safe and warm and comfortable option.

Or I could take a risk, I could enter the danger zone on purpose, I could make a sacrifice, I could do what I knew I was meant to do. Love is watching someone die.

Outside, the flock of birds raised their wings and flew off into the open air.

My mother came into my room that night to talk to me, to ask me what had happened up in the attic. Her eyes were filled with concern and worry as she looked at me. A lump started forming in my throat the moment she sat down on the bed next to me, but I felt an urgent need to prove to her that I was all right.

“It was nothing, Mom,” I told her, brushing off the incident like an annoying fly. “He threw a fit because I went up there alone — apparently nobody’s allowed in the attic unless he’s there too.” I rolled my eyes, to show that it had been silly, nothing big, just something stupid. She still looked anxious, her brow furrowed.

“I just want you to be careful, Sphinxie,” she said. Sighing, she put a hand to her forehead and smoothed her hair back from her face. “Well, we’ll be leaving in about three days.” She said that last part more to herself than to me; it was a reassurance that there was only a small amount of time left in our visit, that nothing too horrifying could possibly happen to me in only three days.

“About that,” I said slowly. My tongue was sticking to the roof of my mouth. I knew what she was going to say when I declared my intentions. She was going to be a mother and insist that I come home. But I had to try. I had to try.

“What?” my mother said, and I took a deep breath.

“I’m not leaving,” I stated, supposing that I might as well put it right out in the open.

My mother opened her mouth and froze that way for a moment, shocked, before she recovered enough to speak. “What are you talking about, Sphinx? Of course you’re leaving.” Her voice was firm, but I sensed a quiver of emotion underneath the outer shell of stern parental insistence. “We have things to do at home, and —

”

I started talking again, interrupting her before she could say anything more. “I have to stay, Mom. I just really have to. I have to stay until he’s gone, Mom, I gotta stay with him.” I was talking faster than I meant to. “He’s so empty, Mom, he doesn’t think he has anyone but himself. He’s always alone, even when there’s people all around him. And I don’t think he’s ever been happy, not really, he’s —”

“Sphinxie,” my mother said, her voice cracking, “I know you want to help him, but you can’t make him better. You can’t make him happy.”

“But I can try!” I said, my voice rising, louder, louder. “He’s got less than a year! I think he should get a chance to be happy, don’t you think? And maybe I’m that chance. He asked for me, he wanted me to come here!” It seemed so clear to me, it made perfect sense. And didn’t mothers always teach you to be unselfish, to put others before yourself?

“Sphinx —” My mother tried to speak, but I cut her off abruptly.

“And think of Leigh, Mom! Don’t you think it would mean something to her if one person other than herself stuck around to watch her son dying young and broken? If one person other than herself cared enough? I’m staying, Mom. I have to do this. I really have to.”

My mother’s mouth quivered.

“Sphinxie, he might hurt you again,” she said, taking my hand. “I can’t let that happen.”

But you already did, said a quiet little voice in the back of my head. And your plan for me broke and now I have to make the choices. And you were the one who told me, Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

I lifted my head and met her eyes. I squeezed her hand and attempted to smile, if only to keep myself from crying. “He’s just a kid, Mom. And he’s dying.” I squeezed her hand again, and her fingernails dug into the skin of my palm. “What if it were me, Mom?” I asked. “Wouldn’t you hope that someone would do for me what I want to do for Cadence? Wouldn’t you want someone to stay with me?”

She bowed her head and didn’t say anything. Maybe she was realizing her part in it all. I hoped she was.

“You would,” I said assertively. “I know you would. Anyone would.”

When I went to sleep that night, I dreamt that I went up to the attic by myself and found a blue heron lying on the floor in front of the huge canvas, its wings twisted and broken.

I woke up to rain pattering against the windows and roof, a clap of thunder echoing in my ears.

“Not a very nice day, is it?” Leigh said during breakfast. “I thought we could go out and do something today, but I don’t know if I want to go out in this weather.”

“I certainly don’t,” said Cadence at once. He inclined his head toward me, his eyes softening. “What do you think, Sphinx? Wouldn’t you rather we just stay inside today?”

“It’s pretty nasty out,” I admitted, looking over at my mother. She dropped her eyes to her plate, as though she hadn’t been looking at me just a moment before. We hadn’t reached a resolution, nor any kind of decision, the previous night: We had just talked until two in the morning and cried, and neither of us could fully understand where the other was coming from. I bit my lip. It was Friday now, leaving only two more days before it was Monday and we left on another flight in the afternoon, flew out over the wide ocean, and crossed over into another time. It’d be morning when we got home, if we left in the afternoon. It would be like starting the day over again.

“I always hated thunder when I was a little girl,” my mother said thoughtfully. “It scared me out of my wits.”

“But I loved it,” Leigh said, grinning. “I used to try to convince Sarah here that it was the most beautiful sound in the world.”

“And she never succeeded,” my mother told us, laughing. “I thought she was crazy.”

“Thanks a lot,” Leigh said teasingly. “I still love it, you know. I just hoped that we could get out again today. It was fun when we went to the movies, wasn’t it?” She left out the part where we went to the restaurant, I noticed. I wondered what the waitress had done with the money. She hadn’t really known what it was for; she had just thought that Leigh was some rich pushover with a spoiled, rude son. I wished I had stopped to tell her. I suddenly wanted her to know Cadence’s name.

“Well,” said Cadence, shaking his blond curls out of his eyes and pushing his chair back from the table, “I’m going to paint.” He stood up, leaving his plate on the table, and loped off in the general direction of the attic, his arms crossed over his chest.

“Why don’t we all paint today?” Leigh suggested, looking timidly toward Cadence for approval. “Would that be all right, Cay, if Sarah and Sphinxie and I came up and painted with you? We’ll just use regular paper instead of a canvas.”

Cadence stopped with his back to us, and his arms unfolded themselves; his head tilted to one side, and I knew that he was thinking: Did he really want us painting in his inner sanctum? But then he turned around. “Yes, that’s fine,” he said curtly, then strode briskly off toward the stairs. By the time we got up to the attic, he was already at work, standing before that gargantuan canvas, filling it up with more blue.

Leigh had a stack of computer paper and three paper plates for us to put our paint on. We went over to the shelves where the tubes were lined up, neatly organized according to color. I ran my hands over them, and they were cool to the touch.

“Is there any paint we shouldn’t use?” my mother asked Cadence before we made our selections.

“Don’t touch the blues,” he said, never once taking his eyes off his work.

“Okay,” I said, and reached out.

I took a light purple, a pale brown, a buttercup yellow. My hand hovered over a robin’s-egg blue before I quickly remembered. Carefully, I squeezed my chosen colors out onto one of the paper plates. As I did so, my eyes darted over to my mother, who was busy collecting her own colors. I felt like we were tiptoeing around each other, like I’d opened up some kind of a rift by telling her about my decision to stay. But wasn’t that how people grew up — opening rifts, cutting boats loose from their docks, until it was easy to step away and live your own life? And people were supposed to grow up faster when they had to deal with tragedy. I guessed it was normal, but it still made me feel vaguely sick.

Cadence was suddenly beside me, the tube of robin’s-egg blue in his hand. Slowly, he unscrewed the cap and then made the tube hover over an empty space on my paper plate, in between blobs of brown and purple. For a moment, I thought he was taunting me; I almost expected him to yank the paint away. But then his fingers clenched around the tube and a circle of robin’s-egg blue appeared on my plate, bright and beautiful. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw my mother and Leigh watching, and an involuntary feeling of pride that Cadence had chosen to offer one of his blues to me, and me alone, swelled in my chest.

Once he’d finished pouring out the blue for me, I knelt in a little semicircle on the attic floor with my mother and Leigh. My mother had picked out pinks and greens, and Leigh had reds and purples. Leigh had taken a glass mason jar filled with brushes from one of the shelves, and put it out on the shelf within easy reach of all of us. I noticed an empty jar on the shelf, and filled it with water from the sink so that we could wash our brushes. And then we began, there in the attic.

I painted a table with my brown, and above it a long, wide rectangle of yellow. I put lines across the yellow with the brown, making window slats. The window panes themselves were the blue, the sacred blue that had been forbidden to everyone but me. Around it all, I spread the purple for a background, and then with the brown I made lines to show that there were walls and a floor, instead of just a lavender mass. I made the yellow come in through the window in rays and land on the surface of the table. It was a lopsided table, with stick legs that could have been painted by a five-year-old. Typical for me. I’ve never had any talent for art.

Beside me, my mother was painting a flowering vine. Long green tendrils swirled over her paper and burst into p

ink flowers. She borrowed some of my yellow to add detail to her petals, and then took some of my brown to make a background: the crisscrossing lines of a lattice. Next to her, Leigh’s reds swirled over her paper in a way that reminded me of Cadence’s work. The strands of crimson formed the shape of a bright red woman holding a little, deep purple child in her arms. The woman’s hair rose up from her head in jagged streaks like lightning and turned purple at the ends, shooting up into the top of Leigh’s paper and becoming billowing clouds.

“You’re really good,” I told Leigh, turning my head sideways to see her picture better.

“Oh, thank you, Sphinxie,” she said, but she kept her head bowed over her paper, her blonde hair falling forward and hiding her face from view. After a moment, she looked up. “Can I see yours?”

I dutifully held up my painting, feeling slightly ashamed of how childish I thought it looked.

“I like your style,” Leigh said. “It reminds me of some famous artist’s style — I can’t remember whom I’m thinking of …”

I looked down at my work. “I don’t think it’s very good,” I confessed. “The table looks silly.”

“No, it doesn’t,” Leigh told me. “It’s simple, but it has elegance.”

“Thanks,” I said, feeling pleasantly surprised by her comments.

“What do you two think of mine?” my mother asked, pulling her brush away from her paper with an air of decided finality. “I went a little crazy with the swirls.” Her vines had grown out of control on her paper, looping around each other and clinging to her brown lattice, leaves and flowers shooting out this way and that.

Breaking Butterflies

Breaking Butterflies