- Home

- M. Anjelais

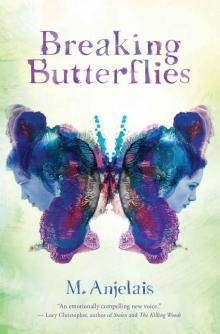

Breaking Butterflies

Breaking Butterflies Read online

To all those who chose to live when they felt like dying, to 29:11,

and to RRRK, who was not afraid.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

When my mother was a little girl, she walked to the playground by herself every day after school. I can picture it easily; photos of her as a child are almost indistinguishable from photos of me when I was little. I used to look at her old yellow-edged school photographs a lot. My mother had a shy, quiet look, a round face, and the same straight brown hair I used to have, though in every picture hers was pulled back from her forehead in two tight little pigtails.

She was lonely when she was little. No one ever asked her to play; she was the clumsy one whom nobody sensible wanted on their team, the timid one who was too chicken to climb on top of the monkey bars. It was the same for me. While other children swirled over the jungle gym and slides in a frenzy of make-believe and hide-and-seek, I would sit by the swings on my own, kicking at the dust. We were two of a kind when we were really young, I can tell. But that was before she met Leigh, and long before I learned how to be strong.

I don’t know much about what happened before Leigh, about the lonely time. All that was just a vague prologue; meeting Leigh, and what happened after that, was the real story. That was what I’d grown up listening to my mother tell and retell, until I’d heard it so many times that I had the dialogue memorized and could whisper the whole thing to myself if I wanted to. Not only was it about my mother, but it was about me, too. In a way, it was the beginning of both of us. And I treasured that story so much that I used to let it own me. Looking back now, two years gone by since everything that happened when I was sixteen, I think perhaps that was my first mistake.

My mother’s part of the story started on a Tuesday, a week or so before her seventh birthday. She’d arrived at the playground and found her usual swing occupied by a girl wearing a pink tutu over her clothes. The girl had a pair of rhinestone-studded sunglasses perched on her head, and from her feet dangled her mother’s shoes, red and high-heeled. She was swinging her legs back and forth contentedly, admiring the shoes, but she looked up when my mother drew near. Her hair was blonde and wavy, and reached down to her waist. My mother never mentioned being jealous of it, but I had a feeling she must’ve been.

“What’s your name?” the girl said.

“Sarah,” whispered my mother. I used to move my mouth along with my mother’s as she told this part of the story, echoing her lines.

“Last name?” prompted the girl.

“Quinn,” said my mother hesitantly.

“Sarah Quinn,” repeated the girl. She looked up at the sky, and back down at her pumps. “That sounds like a superhero’s name. The name they have when they’re not doing hero stuff, I mean. Like Clark Kent is Superman’s regular name, you know?”

“Yeah,” said my mother. “What’s your name?”

“Leigh Latoire,” answered the girl.

My mother said she was in a state of faint awe. “That sounds like a movie star’s name,” she said, which was exactly what I always thought whenever I heard this part.

“Thank you,” said Leigh graciously. “But I don’t want to be a movie star when I grow up. I want to be a pirate queen.”

“I want to be a vet for horses,” said my mother, who was currently in The Horse Phase, which is an important part of growing up (I myself have gone through The Horse Phase, meaning that I am definitely a normal girl).

“That’s nice,” said Leigh politely. She had not gone and would never go through The Horse Phase, because she was out of the ordinary. My mother understood this right away. She stood leaning against the frame of the swing, and looked at Leigh — at the rhinestone sunglasses, at the red high-heeled shoes, at the tutu, at her long, flowing blonde hair, at her eyes, which were a pale, pale blue. And as she looked, she began to feel like she really was in the presence of a queen. Perhaps even a pirate queen.

“Hey,” my mother said, “do you want to come to my birthday party? I invited everyone in my class at school.”

“Sure,” said Leigh. “Sure, I’ll come to your party, Sarah.”

She was the only one who did.

“Where are all the kids from your class?” she asked as she came into my mother’s backyard, which had been festooned with cheap streamers and wilting balloons. My mother was sitting on her back porch steps, a ridiculous cone-shaped party hat on her head, feeling terribly ashamed of her empty party. When she told me this part, I could feel her embarrassment in my own chest, heavy and pressing down toward my stomach; there had been parties like that for me, too.

“They didn’t come,” muttered my mother, and wiped her nose on the back of her hand.

“Well, I came,” said Leigh, handing my mother a present wrapped in pink sparkly paper. “Go on, open it.”

I always imagined the pink paper unfolding and falling away as though I were opening it with my own hands. Leigh had given my mother toy horses, a set of four of them — matching mothers and foals, one pair of palominos and one pair of bays.

“Do you like them?” asked Leigh eagerly.

“I love them,” my mother said. The horses were flocked and soft. I knew because the first time that my mother had ever told me the story, she had taken the horses down from where she kept them on her dresser and let me touch them.

“I thought you would,” said Leigh. “Let’s play the party games now!”

She and my mother played egg-and-spoon race, pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey, and scavenger hunt. They beat the piñata into a rainbow assortment of torn pieces. They had two pieces of birthday cake each, and they divided the contents of all the unclaimed goodie bags between themselves. They made a fort out of two lawn chairs and an old sheet, and carried all of the candy from the piñata into it, where they devoured it in secret. My mother said it hadn’t mattered that there were only the two of them, with no other guests around. Whenever my mother described it, she made it sound like the best party there ever was. I imagined it in extra-saturated color, a rainbow bursting out from a backdrop of muted vintage tones.

It was during this party that Leigh, as her little fingers unfolded the comic wrapper from a piece of Bazooka gum, had asked my mother to be her best friend.

“Really?” my mother asked.

“Well, don’t you want to?” Leigh’s eyes were large.

“Of course,” my mother said. They had both laughed. When I was really little, I used to like this part. It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship, the end of my mother’s childhood loneliness — a good thing, I always thought. But there would come a time, when I was older, that I wondered how differently my life would have turned out if Leigh had never been on the swing that day, if she had not been the sole guest at my mother’s party. And I wished, sometimes, in a dark place in the back of my head, that my mother’s answer to Leigh’s offer of friendship had not been a happy agreement.

Leigh had instructed my mother to run inside and get a pin, saying eagerly, “We have to become blood sisters!” And my mother dutifully went into her house and brought out a pin.

Leigh took it from her wit

h the utmost ceremony and stabbed her thumb, squeezing it to bring the blood to the surface before handing the pin back to my mother, who bit her lip nervously. She used to feel the same way about blood as I do: beyond queasy.

“Go on,” urged Leigh. “You can do it. It doesn’t hurt that bad.”

My mother pricked her thumb, and when a little drop of crimson welled up on the tip, she was terribly proud of it, even though she tried not to look at it for too long. Leigh pressed her thumb against my mother’s.

“There,” she said, pulling her hand away and sucking on her thumb. “We’re blood sisters now, and best friends forever.” She had paused thoughtfully before finishing, “Let’s plan out our lives.”

“What do you mean?” my mother asked, wiping her own thumb on the fort sheet. At seven years old, she hadn’t known that the most important part of the story was coming next. But as a grown woman, telling it to me, she knew, and she always dropped her voice at this point and leaned in toward me, her eyes sparkling.

“Let’s just make a plan, all right?” Leigh had said. “I’ll go first.” She took a deep breath, and began, “When I grow up, I want to be a pirate queen, but if that doesn’t happen, I want to be a fashion designer and make fancy clothes. I’m going to have two houses, one in the United States and one in England — if I end up being a fashion designer anyway. If I’m a pirate queen, I’ll live on a ship. No matter what I am, though, I’m going to have a kid — one kid, and it’ll be a boy, and I’ll name him Cadence, the most beautiful name I have ever thought of. And of course, all through my life, I’ll be best friends with my blood sister, Sarah Quinn.” She stopped in order to breathe, and said, “There, see? That’s my life. Now plan yours.”

“Okay,” my mother said, and she thought for a moment. “Well, when I grow up, I want to be a vet for horses. If that doesn’t happen, I want to work in advertising, just like my mommy does. I just want one house, and it’ll be in the United States. I’m going to have a kid too, just one — a girl. And I’ll name her … Sphinx. I learned that word in history class, but I think it’s pretty. I can call her Sphinxie as a nickname. Oh, and all through my life, I’ll be best friends with my blood sister, Leigh Latoire.”

The other spoken lines in the story were half-guesses, what my mother thought that she and Leigh had said, but the plans were exact quotes. My mother had never forgotten the words, and after years of hearing them repeated to me, neither would I. They were written on the inside of my mind forever, like an internal tattoo.

“Since you’re having a girl, can she marry Cadence?” cried Leigh excitedly. “Then when they have kids, we’ll be grandmothers together!”

“Yeah,” agreed my mother. “Yeah, they’ll be best friends, and then” — here was the part she didn’t tell me until much later — “they’ll get married.”

She left the fort for a minute and returned with the set of four horses. “Look, Leigh,” she said. “It’s me and you and Cadence and Sphinx. You and Cadence are the palominos, and me and Sphinxie are the bays.” She opened the box and took the horses out. “Here,” she said, handing Leigh the palominos. “They’re friendship ponies.”

“And reminders,” said Leigh, stroking the palominos. “They’ll remind us to follow our plans, for always.” She picked up the bay foal and held it in one hand, the palomino foal in the other. Slowly, she touched their noses together in a kiss. “Cadence and Sphinx,” she whispered.

I learned in health class at school that when a little girl is born, she already has all of the eggs she will ever have inside her. So, in a way, I had experienced the story firsthand. Cadence and I were there as our mothers made their plans, as they named us, as they betrothed us. As Leigh touched the foals’ noses together, we were dormant and sleeping inside. And perhaps we stirred slightly, knowing somehow that the plan would hold and we would someday burst out into the world as red-faced newborns, ready to grow. We, under the old sheet of the fort, two eggs out of millions.

We were there.

My mother went into advertising. She prepared layouts for magazine and newspaper ads, and her lettering was beautiful. She met my father at work, and they dated for a very long time before he asked her to marry him. Her wedding dress was white and puffy. She and my father moved into a house in Connecticut, a house with an extra bedroom for a baby, with a nice backyard for a set of kiddie swings that would become my favorite place to play.

Leigh became a fashion designer. She had clothes with her name on them in the high-end malls, and she sat in the front row at glitzy runway shows, watching girls with high cheekbones slope down the catwalk wearing dresses she’d created. She bought a house that was bigger than my mother’s house, in a wealthier neighborhood several miles away; a year later, she bought her house in England, and flew back and forth between the two. She met her husband at a fashion show, and they dated on and off for a very long time before he asked her to marry him. Her wedding dress was a viridian green — she made it herself. I saw photos of it once and couldn’t decide how it made me feel because, though it was beautiful, it made my mother’s dress look old-fashioned and fussy. It was in a class all its own.

Even after they got married, my mother and Leigh remained best friends; they met for coffee, shopped together, talked on the phone, sent cards, and invited each other to one thing and another. Leigh designed a dress inspired by one that my mother had worn as a little girl, and named the design after her. My mother worked on advertisements for Leigh’s clothes. She cut them out of magazines when they were printed and kept them in a box, carefully saved. Every so often, I looked through them, leafing through the glossy pages. And always, the palominos stood behind a glass pane in a china cabinet in Leigh’s England house, and the bays were on my mother’s dresser.

Leigh was the first to find out that she was pregnant. She teased my mother about it, saying that she’d beaten her to it and urging her to hurry up. My mother caught up quickly: Only two months later, she received the news that she was pregnant too. She’d gone with Leigh to her ultrasound appointments, and had been there when the technician asked Leigh if she wanted to know what sex the baby was. Leigh had squeezed my mother’s hand nervously; she was afraid that she was going to have a girl and the plan would be spoiled. But the technician pressed down on Leigh’s stomach and informed her that it was a boy, and my mother laughed out loud. It was all going according to plan.

“It’ll be my turn soon,” my mother had told the technician. “You’ll be looking at my little girl.” She patted her stomach. When her turn came, the same technician brought my image up on the ultrasound screen and announced that, yes, she was looking at my mother’s little girl. Leigh and my mother set aside dates for baby showers.

My parents decorated the extra bedroom for me, all in pastel pink. I would end up leaving it that way. The furniture changed as I grew, of course, and when I hit my preteens I started putting up posters and photographs of my own, but even now I’m still pretty happy with my soft pink walls.

Leigh hired someone to come in and do Cadence’s room, but she didn’t have them do it in blue. Light blue for a baby boy was too ordinary for Leigh. She created a color scheme based around a swatch of green fabric, the same fabric used to make her wedding gown. She had someone paint trees on the walls, and a night sky on the ceiling. When the lights were turned out, the stars glowed in the dark.

At the baby showers, my mother’s friends brought pink onesies and footie pajamas, rattles shaped like flowers, a mobile with plush butterflies hanging from it, soft baby blankets with roses embroidered on them, cards that welcomed a little girl. Leigh brought me a gigantic stuffed zebra with a purple ribbon tied around its neck. Made out of all organic fibers, the tag said. Tag made out of 100% recycled material. It’s still at the end of my bed, a formidable presence that new friends always ask about when they enter my room for the first time. Leigh’s friends brought Cadence things like that: eccentric stuffed animals and rattles made of wood, classy in their simplicity. My mo

ther brought him a huge teddy bear and a set of blue onesies with little trucks on the front.

Then suddenly, we were born, pushed out into the air and bright lights, the cords connecting us to our mothers severed. My mother went over to Leigh’s house and they sat in the airy living room, spinning an Enya CD in Leigh’s stereo system, nursing us on the wide sofa. And soon enough, watching us crawl over the wooden floor. Lying on our plump stomachs, reaching for the toys scattered over the living-room rug. Standing. Stumbling forward. Growing like weeds, from two eggs to two babies to two toddlers to two children.

There was nothing particularly remarkable about me as a little kid. I looked a lot like my mother had; I was not as shy as she had been, but I was not particularly outgoing, either. I never initiated the games when my friends came over; I politely said hello and showed them where my toys were and waited for them to tell me what to do. If there was ever a disagreement, I’d flee to my mother, pressing my head into her chest to avoid dealing with the conflict. While my peers busied themselves grabbing each other’s toys and giving each other experimental whacks across the face, I already understood that certain things made people feel badly, or made their bodies hurt. Empathy, perhaps, was my only talent — I never showed very much promise in any other areas.

Cadence, on the other hand, was one of those children everyone was stunned by. He was an excellent artist even when he was little. While I was just beginning to draw stick figures, he was drawing amazing pictures of people, like some child prodigy. It was like that in almost every part of life: While I still stuttered and baby-talked, he amazed people with his long sentences and perfect speech; while I clung to my mother, he was totally independent, and he always got what he wanted. And while I was a slightly pudgy, brown-haired child, indistinguishable from the masses of little girls in the world, he was a striking little wisp of a kid, his face a sharp white angle surrounded by wavy blond hair like Leigh’s, his eyes a fierce shade of ice blue.

I always felt vaguely stupid when I was around him. I was simply too ordinary, while he was this vision of talent and good looks, whirling through life and dazzling everyone with his greatness. I never really hated him for making me feel less than him; I was just in awe of him, like my mother had been in awe of Leigh when she had met her at the playground all those years ago. I thought of him as shining, always shining. But light can be blinding; it can shine so hard into your eyes that you don’t realize what’s behind it — and then, like a car hidden behind glaring headlights, it hits you at full speed.

Breaking Butterflies

Breaking Butterflies