- Home

- M. Anjelais

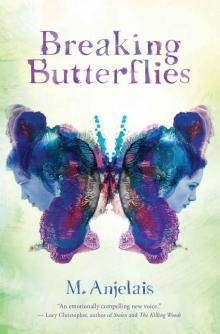

Breaking Butterflies Page 13

Breaking Butterflies Read online

Page 13

And there was no cure. Cadence would stay this way for the rest of what little time he had left. Trapped, no way forward, no way out. Staring and staring, imitating everything so perfectly, shining and shining but so, so dead. He would never really smile. He would never really cry. He would never really fall in love, no matter how softly he could speak or how gentle his hands could be. And he would never understand what he was missing. I felt a lump rising in my throat and I thought, This is it, this is it right here. I’m feeling sorry for him. It was reassuring. Even if the scar never faded from my cheek as I got older, even if I was shy and a nobody at school and the boys never noticed me — I was still normal, I was all right, I could feel it all. The realization jolted me. And at that moment, a few rooms over, he was alive, breathing just as I was, and he was cold, just as cold as his eyes, and empty like a dusty ceramic vase.

Suddenly I understood why he was so terribly good at everything. It was because there was nothing else for him to do. He couldn’t work on building relationships with people. So what was left? For most people, it was people who came first, and hobbies and learning came second. For Cadence, there was no people element. There had never been. He had literally nothing to do but throw himself into other things — working, pushing, succeeding at all of them — shining, as I used to see him. But people were still missing from his life, just as they were missing from the paintings on the walls of his bedroom.

The digital camera was lying out of its case on my bedside table. I had filmed Cadence secretly for the third time that day, not too long after he’d told me his terrible secret. We’d just finished dinner and he had sat down on the couch and swung his feet up onto the coffee table and fallen asleep. His head was lolling back against the top of the couch, his blond hair spreading over the dark leather of the furniture. Asleep, his face lost that wall-like quality he sometimes had and opened up slightly, becoming more childlike, more human. And more sickly. His eyelids looked thin and translucent, his cheekbones pressed out, creating shadows below themselves, and in the light from the living-room lamp, I could see a thin web of blue veins spreading out from his temple and over his forehead.

Vivienne had left for the day, and Leigh was still in the kitchen, talking to someone on the phone, her back to the living room. I was trying to ignore her. I didn’t want to think about her yet, about what she’d done. Determinedly, I’d focused the camera on Cadence’s still face and filmed, just a minute of him in sleep. Then suddenly my hand shook. What if he wasn’t sleeping? What if I was filming him dead? I’d turned off the camera and put it down on the coffee table, and then reached forward to touch him, shake him. I hesitated, afraid that he would wake up angry with me for touching him … but what if he didn’t wake at all?

I settled on raising my foot and using it to nudge his ankle. He shifted, and his head turned to the side. I let out a breath of relief. My heart was beating at a faster pace than usual. I had been so scared when I thought he was gone, when I thought he had died in front of me, when I thought that the person I had loved and feared in equal measures had left my life.

As I watched the minute-long clip over again before I went to bed, that same feeling rose in my chest, making me feel very small. It was dawning on me that someday not very far in the future, I would see Cadence after he had died — if I managed to stay until then, as I intended. The shining one would go to sleep and never wake up, and I would see his body when the life had left it. I’d see those terrible, beautiful eyes without any light in them. All of a sudden, I wasn’t sure if I could handle that.

And now, alone in my room, the laptop put away, I wasn’t sure if I could handle what came before that, either. If Cadence was a sociopath — if he was dangerous, if he was that ill — then what would he do in the days before his death? What would he do to me?

I took a shaky breath. In that moment, I wanted to call my mother and say that I wanted to go home. If I told her the secret, I knew she would immediately buy me a plane ticket and rush me out of there. And I’d be safe. All it would take was one phone call, and I could get on the phone right now.

But you have to be here for him no matter what, said a small voice in my head. You have to make the most of the small amount of time he has left. You’re meant to be here, you’re meant to do this. You know that. Even Cadence knows that. He said we were made for one another.

I reached over and switched off the lamp on my bedside table. In the dark, I pulled the covers up to my chin and curled into a ball. I suddenly wished that my mother were still in the other guest room, just in case I needed to be little again and run into her room during the night.

The next day, we all went out after breakfast. Leigh drove us into a little village near to her house, mainly made up of small, family-owned shops and restaurants. It was the perfect picture of what everyone thought of as a little British village. Quaint. Cute little houses and buildings, all in a row, all looking like a kindly grandmother’s abode. Flower boxes in all the windows. Chickens pecking around some of the yards. I thought it was absolutely adorable. It reminded me of a kids’ picture book.

“I love this place,” Leigh said. “It’s so picturesque, and the shops have some really cute stuff in them.”

Cadence seemed either unimpressed or depressed, if he was capable of feeling that way. He pulled his jacket more tightly around him and lagged behind us, his eyes hidden behind a pair of thin sunglasses.

In one of the shopwindows, a cage filled with young budgies sat in a sunny spot. The birds darted all over the place, chattering to one another and flapping their clipped wings. Leigh stopped in front of the window and tapped her finger against the glass, making the birds swivel their heads to look at her.

“I had a budgie when I was a teenager,” she said, smiling. “His name was Orville.”

“That’s cute,” I told her, standing next to her in front of the birds. Cadence came up next to me, and I asked him, “Do you like birds?”

“Yes,” he said after a moment of contemplative silence. He took off his sunglasses and peered at them, his eyes darting around to follow a particular one: blue and white, with a dash of yellow at its throat.

“Do you want one?” Leigh asked eagerly, almost leaping forward. The fact that Cadence had shown a relatively cheerful interest in something had sprung her into action, as though she was hoping she could freeze time and keep him that way. “Do you want that one you’re watching, with the yellow on it?”

“All right,” said Cadence, surprising me. He didn’t strike me as the type that would enjoy caring for a pet, and I wondered why a common budgie had caught his interest. We went inside the pet shop, a little bell ringing over our heads as we did so. We watched as the man came out from behind the counter and opened the budgies’ cage, as Cadence pointed out the bird he wanted, as the man captured it in his fist, as easy as could be. He put the bird in a little cardboard box with air holes on the top and set it down on the counter to wait while we browsed through cages and bird toys, seeds and dried-fruit treats.

“I want to get one of those cages that hangs down from a little pole,” Leigh said. “That’s the kind I had for my bird. It was really convenient, you could just move it around. I used to put it out on the porch so he could get some fresh air.” The man showed us where that type of cage was located in the shop, but Cadence didn’t seem interested in picking one out, so Leigh chose instead: a circular cage with a domed top, metal swirls painted a robin’s-egg blue.

We paid for everything and left, not wanting to leave the bird in the box while we browsed around the village. In the car on the way back to Leigh’s house, Cadence held the box on his lap, and the bird chirped softly from within. Occasionally, it tried to flap its wings, making little thumps against the cardboard.

“Poor little guy wants to get out,” Leigh said sympathetically. “What do you want to name him, Cadence?”

“I’m sure I don’t know,” Cadence said dryly, his slim fingers tapping lightly against the side of the

box. “What was yours named, again?”

“Orville,” Leigh said brightly. “For one of the Wright brothers. The guys who designed the first airplane.”

“This one could be Wilbur,” I offered. “For the other brother.”

“Fine. Wilbur it is,” said Cadence, smiling at me. Inside the box, the newly christened Wilbur made little scratching noises with his feet against the cardboard bottom. And I smiled too, feeling pleased that Cadence had allowed me to name him.

“I hope he’s all right in there,” Leigh said. “He doesn’t sound happy.”

When we got back to Leigh’s house, we set up the cage in a relatively empty corner of the living room before opening the box. The budgie stared up at us from within for a split second before flapping his clipped wings and fluttering a few feet out, making us all jump. He landed on the floor not more than a few paces away. Leigh reached forward and caught him neatly in her hands.

“Got you!” she said triumphantly. “Sphinxie, open the cage door for me, please.” I unlatched the little hook and held it open for her so that she could deposit Wilbur inside. He fluttered to one of the perches, looking about with bewildered eyes that were like black beads in his head.

“He looks totally confused,” I said, chuckling. “He’s not used to being in a little cage without other birds to hang out with.” His little head was swiveling around, looking at each of us in turn. Cadence stepped up and leaned in closer to the cage, making the bird focus on him. The little yellow beak opened slightly, as though preparing to bite if necessary.

“Silly bird,” said Cadence softly, sticking a finger through the bars of the cage and flicking one of the mirrors that Leigh had hung up. “Silly, silly bird.”

“He’s not all that silly. Birds are actually quite intelligent,” Leigh pointed out. She set out the little plastic food dishes that had come with the cage and tore open one of the packages of birdseed. Carefully, she poured out enough seed to fill one dish, and then sent me to the kitchen sink to fill the other with water. “We have to make sure that he always has food,” she informed us. “Birds need to eat all day.” She set the seed dish down on its little ledge in the cage, and the budgie slid down the bars to reach it, pecking eagerly.

I thought there was something very desperate and sorrowful about the way that Leigh had carefully poured out the birdseed and reminded us that we must always make sure the dish was full. She was jumping around, like a child excited by her new pet, but there was something very heavy about her excitement. It was as though she was overcompensating with her happiness lest she show any sadness. Cadence had wanted that bird so badly in her head, and she had bought it for him … but he had not responded with normal joy, as usual. I thought she was trying to feel the childish excitement and happiness for him, and it was saddening. I was starting to understand. She was so desperate. Feel this, feel this, feel it.

It was like that for Leigh every day, in everything she did. And it must have been that way ever since Cadence was born, and he grew up strange and detached, a wall behind the emotions that he had taught himself to fake.

When I realized that, I thought that at last I understood what he wanted me there for. I was the first person he’d really learned to take emotional cues from, the first person he’d studied. Once upon a time, playdate after playdate, he’d modeled his mask by looking at me, like the day that he killed the butterfly and I’d unknowingly taught him that he was supposed to cry. I was the model who stood at the front of the art class, my heart on my sleeve, laid bare for the student to try and capture my likeness. And oh, how he’d tried.

He didn’t really have any interest in the bird at all. Leigh and I dutifully cared for Wilbur the budgie, taking turns at cleaning out the newspapers from the bottom, seeing to it that there was enough seed, filling up the dish with fresh water every morning. He seemed happy enough for a caged bird. He fluttered from perch to perch, talked to his reflection in the mirror, and sang when we left his cage in front of the window, allowing him to see wild birds outside. Every now and then Cadence seemed to remember that he was there, and went over to the cage, sticking a finger through the bars and petting the little feathery head.

Leigh and I liked to let Wilbur out so that he could explore the living room; his flight feathers still hadn’t grown back out since we had bought him from the pet shop, and so he would simply run around on the living-room floor, nibbling at the carpet. Cadence would retreat to another room when we did this. I supposed he preferred the bird through the blue lines of the cage bars, but I enjoyed watching Wilbur run around. It was a little release from the serious feeling in Leigh’s house, just following this winged creature, watching his bewildered curiosity at everything in Leigh’s living room.

When I was little, we had a cat, an old cat that really just belonged to my mother. I would try to pick the poor cat up like a baby, and always got scratched for my overenthusiastic displays of affection. Seeing the budgie dart around made me want to get one of my own, from the same little pet shop, and take it home with me as a reminder.

Later, during that same week, we were watching television in the living room. Leigh had Wilbur out, sitting on her lap like some sort of a substitute for a lapdog. He’d become friendly and used to us quickly; he was perfectly content to hang out on your lap. Leigh was petting him rhythmically, running her forefinger down his back over and over again.

I thought Cadence was asleep, or at least dozing. His eyes were half closed, and they weren’t focused on the television set whatsoever. He was starting to sleep an awful lot during the day, something that was hard to see. I knew it upset Leigh too. She didn’t want to watch him getting slower and slower, more and more exhausted as his body gave in bit by bit. I stared at him for a moment, checking, as I always did when I noticed him sleeping, to see if he was still breathing. He was, very slowly. His chest was rising and falling, but almost imperceptibly. His head had fallen to the side and was resting on his shoulder. He’s going to wake up with a stiff neck, I thought. Then, all of a sudden, he woke.

His eyes literally snapped open; they went from drooping peacefully to becoming wide holes of ice blue in his head, all in a matter of seconds. I jumped and looked away, thinking that it would be weird for me to get caught watching him sleep. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw him raise his head and look around the room almost wildly. Had he woken up from a nightmare? His eyes were darting all over the place, seeming never to settle on any particular object or person in the room.

“Cay?” Leigh asked nervously. “Are you all right?”

“Let me hold the bird,” he said, and his eyes stopped finally, resting on the budgie. And for a moment, he stared, watching Leigh’s finger caress the little feathered body, watching how she smiled and imitated the sound when Wilbur chirped contentedly.

“Sure,” Leigh said, sounding slightly confused. She took Wilbur in her hand, rose from the sofa, and passed him to Cadence. He put the bird in his lap and watched for a moment as the tiny beak explored the wrinkles in the leg of his pants. His slender hand reached out and covered Wilbur’s back, stroking him slightly, softly. But then his hand came down harder and harder. Wilbur squawked in protest, but couldn’t get away; Cadence’s hand was practically pinning him, flattening him, his wings and little pink feet splaying out in protest.

“Cadence!” Leigh said, her voice rising. “You’re hurting him!”

Up and down went his hand, harder, harder. The bird screamed, high-pitched and raspy. Cadence’s face was blank and stony. Harder and harder and harder. His eyes burned, brighter, painfully.

“You’re crushing him!” I said, and without thinking, I reached over and grabbed his thin, bony wrist. My fingers met my thumb and overlapped each other; Cadence’s wrist felt fragile in my hand, but he was stronger than I’d imagined. After what seemed like forever, I pried his hand up, off the budgie. Wilbur was silent, but he wasn’t dead: He fluttered haltingly off the sofa and dropped to the floor, where he shook himself and scuttled u

nder the coffee table, trembling. I still had my hand around Cadence’s wrist, gripping tighter than I meant to.

Suddenly angry, Cadence jerked his arm away from me, his eyes narrowing. Before I could think to back away, he had balled his other hand into a fist and tried to punch me in the face, but he missed, only grazing the side of my cheek. I leaped away from him and he came after me, grabbing my shoulders as he got up from the sofa; our feet twisted together, and we fell onto the coffee table in a tangle of limbs and a crash of breaking glass.

I was aware of nothing but Leigh screaming, the bird flapping wildly out from under the table, the table itself seeming to disappear underneath us. And Cadence yelling hoarsely, and breathing hard and fast and roughly, as though his breath were caught in his throat. I was on top of him, I realized.

I rolled off and something crunched painfully under my back. Cadence lifted his hand for no apparent reason and then let it fall back again; it landed on my shoulder, and when I raised my own hand to push him off, there was blood dripping down my palm, coursing down my wrist, and a shard of glass was glistening, stuck cleanly through the palm of my hand.

My voice was trapped in my throat, and I couldn’t move. For a moment, all I could do was stare up at the ceiling overhead, my eyes locked there involuntarily. Leigh was screaming for Cadence and me to stay still, that she was going to call an ambulance. As soon as I heard the word, I started sobbing and yelled back at her, frantic.

“Don’t call an ambulance!” I begged. “Please, Leigh, my mom will freak! Please don’t call an ambulance!” Beside me, Cadence was panting, his hand pressed to the side of his chest. Vivienne came pounding down the stairs; she had been folding laundry on the second floor but dropped everything when she heard the commotion downstairs. She appeared next to Leigh, white-faced.

Breaking Butterflies

Breaking Butterflies